A Collection of Essays

These are a collection of essays I have written over the past couple of years. Most of these were written for my History of Art degree at the Courtauld Institute of Art. During my time at university I studied a huge range of periods and styles, from Spanish Medieval Islamic Architecture to Le Corbusier.

Michelangelo and the Rondanini Pietà

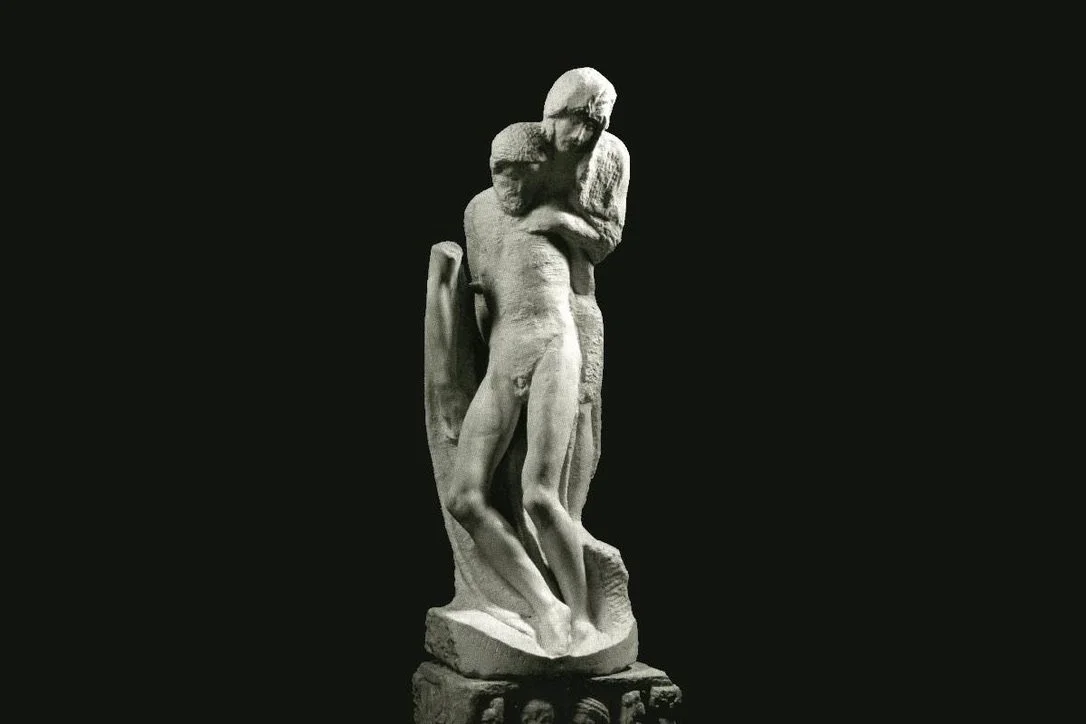

Michelangelo’s final, and incomplete, pieta captures the moment Mary takes the weight of her dead son. The legs, the most finished element of the piece, are giving way and Mary is staggering under his dead weight. There is a sense of their joint collapse, held in the sensual curve of the composition. The curve manages to both show the fall of Christ and the weight on his mother, whilst simultaneously suggesting their potential ascension, allowing the energy of the piece to also flow upwards.

The work communicates exceptional poignancy in the protective lean of the mother, the slump of her son’s body at the moment life leaves it.

Like the drawing of the crucifixion, the faces here remain unfinished and oddly similar to each other. Mary’s face is older, less beautiful than in the Vatican version, but the emotion is still tangible in both her facial expression and her loving hand which merges with Christ.

Like Christ’s legs in both works, Mary’s are unusually bare. Christ’s legs here are delicately carved becoming almost feminine, made vulnerable in their inability to offer support. There is a tenderness in their bend, and it is clear that this is the element most worked by Michelangelo. This is the piece he worked on closest to his death.

During the 1550’s the crucifixion became a fascination for Michelangelo who drew Christ on the cross over and over again. This repetition exists within the drawing here: the overdrawing of the lines means that they begin to flicker and vibrate, a sense of animation in the image and M’s careful meditation and almost ritualised mark-making. This echoes the crude chisel marks on the pieta which are laboured and, like the black chalk marks on the crucifixion they offer an immediate connection to the artist. We see where his aging hands have interacted with the paper or the marble. The crude scrapings of Michelangelo’s chisel in the Rondanini speak not only of the hand of the artist, and his attempts to almost breathe life back into the rib cage of Jesus.

The archaic, over-simplified composition which begins with the simple, straight lines of the cross then offers the triangular composition which, because of the lack of attention to the arms, becomes focused on the vertical.

There is an emptiness to this image. It is dominated by the negative space around Christ’s body. The thin lines that suggest the outlines of Christ’s arms evaporate into the space. Like the Rondanini, both are unresolved and incomplete, tentative and weary.

Michelangelo’s earlier unfinished works hover on the brink of realisation, with their emerging figures and incomplete paintings holding in their incompleteness the possibility of perfection. In both of these works, it is Michelangelo’s mortality that is most apparent. The hope of redemption and salvation would have been much on his mind. Here he is not fulfilling the requests of a patron, he is choosing his subject and approach and trying to keep his hands and eye capable and active. Working in his seventies up to his death, the pieta embodies a combination of M’s own mortality and his dwindling ability/capacity to realise his ambitions in marble.

The sketch carries a similar poignancy in its approximation to the complete and masterful sketches drawn with a decisive hand in his past.

The religiosity of the two works speak to Michelangelo’s devotion and centrality of his Christian beliefs which increasingly inform his life and work. Each piece is like a prayer, each line and mark a meditation on Christ and mortality.

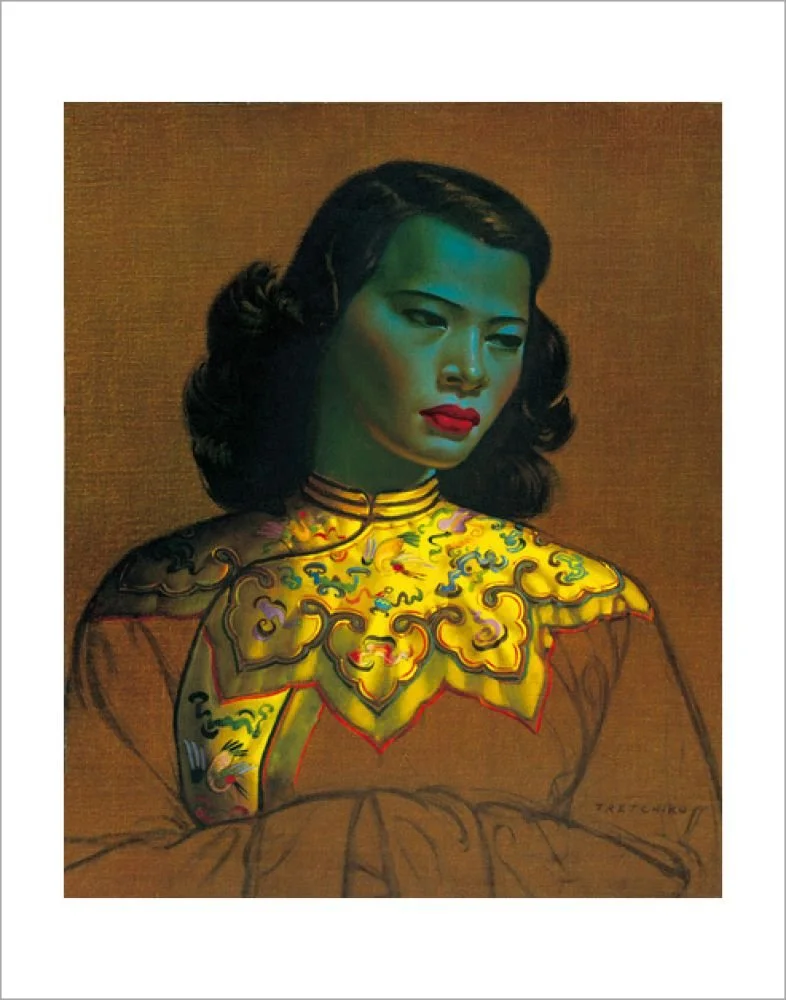

Tretchikoff’s ‘Chinese Girl’

This essay explores the notion of kitsch in the art world. I look at this through the lens of Tretchikoff’s ‘Chinese Girl’, one of the most iconic images of the 20th century. Despite the paintings popularity and cultural importance, there has been little to no academic writing on the work. As a real trail blazer in the art world, I took it upon myself to change that.

Le Corbusier and the symbol of the Open Hand

In this essay I looked at Le Corbusier and the importance of the ‘Open Hand’ symbol. Focusing on his Chandigarh project in India

Michelangelo and the Rondanini Pietà. And a few others

A few different essays i completed for one of my exams, including one about my most favourite bit of art ever.

Michelangelo’s final, and incomplete, pieta captures the moment Mary takes the weight of her dead son. The legs, the most finished element of the piece, are giving way and Mary is staggering under his dead weight. There is a sense of their joint collapse, held in the sensual curve of the composition. The curve manages to both show the fall of Christ and the weight on his mother, whilst simultaneously suggesting their potential ascension, allowing the energy of the piece to also flow upwards.

The work communicates exceptional poignancy in the protective lean of the mother, the slump of her son’s body at the moment life leaves it.

Like the drawing of the crucifixion, the faces here remain unfinished and oddly similar to each other. Mary’s face is older, less beautiful than in the Vatican version, but the emotion is still tangible in both her facial expression and her loving hand which merges with Christ.

Like Christ’s legs in both works, Mary’s are unusually bare. Christ’s legs here are delicately carved becoming almost feminine, made vulnerable in their inability to offer support. There is a tenderness in their bend, and it is clear that this is the element most worked by Michelangelo. This is the piece he worked on closest to his death.

During the 1550’s the crucifixion became a fascination for Michelangelo who drew Christ on the cross over and over again. This repetition exists within the drawing here: the overdrawing of the lines means that they begin to flicker and vibrate, a sense of animation in the image and M’s careful meditation and almost ritualised mark-making. This echoes the crude chisel marks on the pieta which are laboured and, like the black chalk marks on the crucifixion they offer an immediate connection to the artist. We see where his aging hands have interacted with the paper or the marble. The crude scrapings of Michelangelo’s chisel in the Rondanini speak not only of the hand of the artist, and his attempts to almost breathe life back into the rib cage of Jesus.

The archaic, over-simplified composition which begins with the simple, straight lines of the cross then offers the triangular composition which, because of the lack of attention to the arms, becomes focused on the vertical.

There is an emptiness to this image. It is dominated by the negative space around Christ’s body. The thin lines that suggest the outlines of Christ’s arms evaporate into the space. Like the Rondanini, both are unresolved and incomplete, tentative and weary.

Michelangelo’s earlier unfinished works hover on the brink of realisation, with their emerging figures and incomplete paintings holding in their incompleteness the possibility of perfection. In both of these works, it is Michelangelo’s mortality that is most apparent. The hope of redemption and salvation would have been much on his mind. Here he is not fulfilling the requests of a patron, he is choosing his subject and approach and trying to keep his hands and eye capable and active. Working in his seventies up to his death, the pieta embodies a combination of M’s own mortality and his dwindling ability/capacity to realise his ambitions in marble.

The sketch carries a similar poignancy in its approximation to the complete and masterful sketches drawn with a decisive hand in his past.

The religiosity of the two works speak to Michelangelo’s devotion and centrality of his Christian beliefs which increasingly inform his life and work. Each piece is like a prayer, each line and mark a meditation on Christ and mortality.

A Biographical Approach to the General, Sir Redvers Buller Monument

In this essay I consider the Buller monument through a biographical lens, investigating the stages of life the statue has undergone and its possible futures. The ‘biographical approach is … worthwhile because it reveals the way that statuary, in itself, functions. If, step by step, one traces the trajectory…it becomes impossible to regard (it) as inanimate blocks of bronze, the meaning of which is established, once and for all.’

There will also be loads more but I can’t yet figure out how to upload a document yet so just be patient with this page of the website. I’ll get it sorted